What is in a number?

The number over the door is confusing. It looks like the house number. But it isn’t the address. It is the year the original house, the first part of the structure that stands today, was built.

This regularly confuses first-time visitors, tradespeople and delivery vehicles. They drive right by, thinking they’ve either gone too far or not far enough. They always find us, eventually. And we’ve gotten better at giving directions.

But why not take it down?

We leave “1782” on the transom because it is as if the house itself is welcoming those who enter to do so with a sense of curiosity and interest in the story it has borne witness to over 240 years.

It still has that effect on me.

I look at the massive hand-hewn beams that make up the timber frame and wonder about the people who felled the even more massive trees from which they were born. Floor joists visible from the basement are essentially tree trunks with one side shaved flat to accommodate the floorboards above, the bark still on many. They’ve been there, bark on, for 240 years.

Who hoisted them into place?

Who walked the floors they support?

How many hands touched the hand crafted door latches throughout the house?

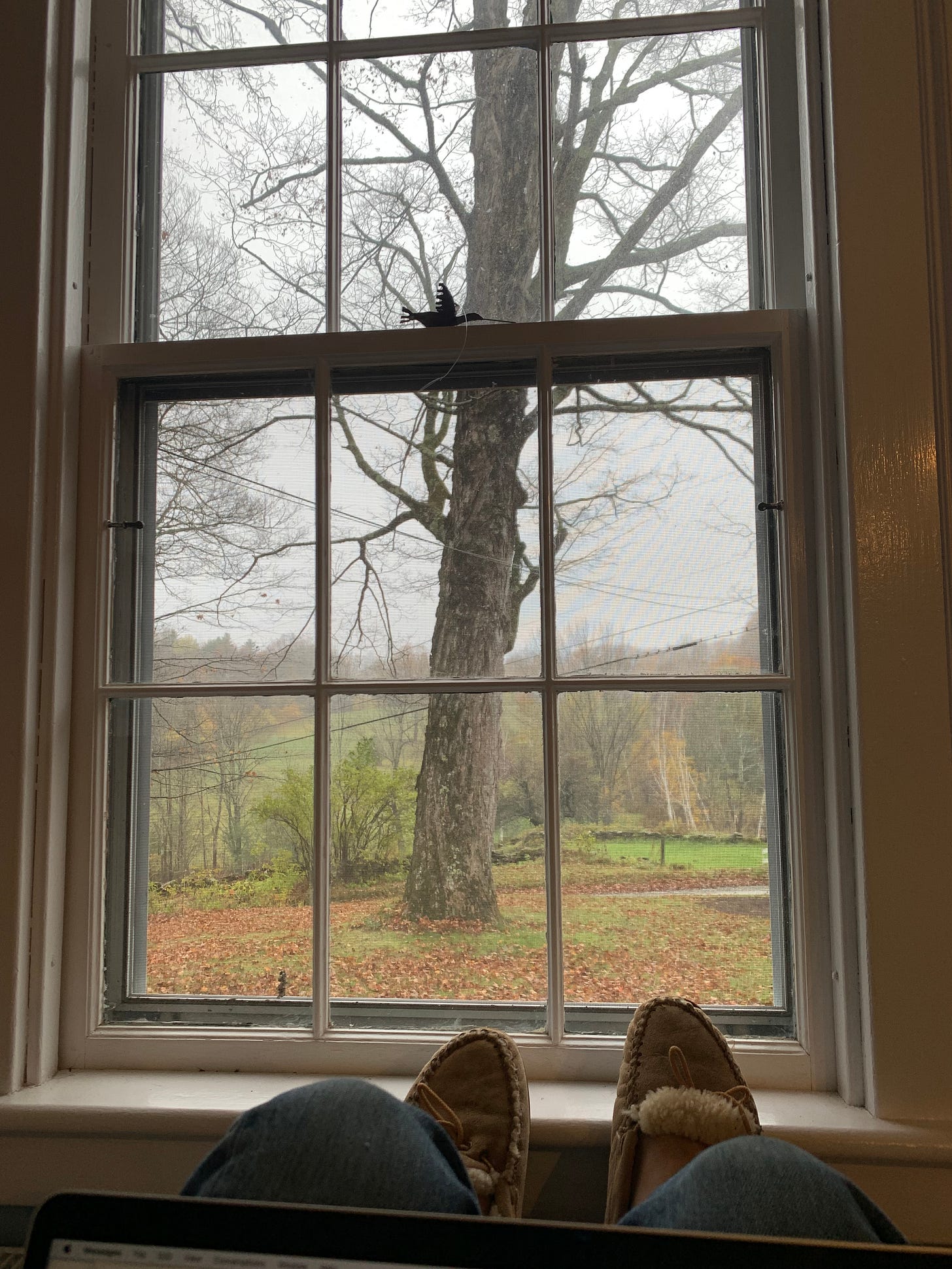

A carpenter friend delights in seeing the hand planed finish lumber, and the way the light follows each dimple of the glorious “imperfections” of hand-shaped boards. Ed delights in seeing the single-hung windows with the peg-hole system for adjusting the sash, saying “those are some very old window frames”. He later sent information indicating this style of window was common from the mid-1700s, and was no longer used by the time the Civil War started.

Who gazed out those windows in the many mornings past, as I often do, and contemplated the day to come?

And on, and on. The whispers of a house with a story to tell.

If houses could speak….

A good friend recently recommended a book to me, “We, the House”.

It is an historical novel in which a house, and a painting that adorns its walls, are able to speak with each other. They share information that helps them piece together and make sense of the happenings in the house, and outside its walls, for well over a century. The narrative gives the reader a window (see what I did there?) on the life of a house, and its inhabitants, from the vantage point of those relatively timeless fixtures of a house. It is creative, entertaining, and sometimes moving.

I’ve yet to hear this house speak directly to me. It’s probably for the best.

Fortunately, the prior owners were good enough to have passed down personal vignettes, as well as some physical documentation, collected over the years. I’ve also found historical accounts. Most helpful were Gilbert Asa Davis’s books on the history of Reading.

One was published on account of the Reading Centennial celebration in 1874, and an updated version when the Reading Public Library (originally funded by Mr. Davis himself, and pictured above) was commemorated in 1899. These books include personal accounts from direct descendants and neighbors of the house’s residents, which confirm and expand on details passed on from the prior owners. The stories beg new questions, and reveal delightful surprises.

First Peoples

The history summarized below is based on the records of European colonizers—they do not mention the people that came before. I’ve much to learn about the earlier history of this land, and particularly the native peoples who first inhabited the area. I plan to do so. I’ve learned enough to know that the past and future of this house takes place on traditional Western Abenaki land, which they call Ndakinna, or “homeland.” I acknowledge the Western Abenaki connection to this region and the hardships they continue to endure.

Moses and Mary (Platts) Chaplin

In 1782, the 22 year old Revolutionary War veteran Moses Chaplin built the house and moved in with his wife, Mary (Platts) Chaplin. They had ten children together in the 26 years they lived in the roughly 1000 square foot single floor structure that was the nucleus of the house that stands today. They were apparently the ninth family to permanently settle in the area since the incorporation of the town of Reading.

Their youngest son, George Washington Chaplin (evidently Moses thought highly of his former commander in chief) provides some interesting details on Moses and their life in Reading. Some highlights from this and other sources:

Moses enlisted in the Continental Army at the age of 16, apparently to escape an “austere and tyrannical brother-in-law” whom he had lived with, in Rindge, NH since his mother had passed some years before, in his birthplace of Rowley, MA.

Despite serving in the Revolutionary War for only a few months of 1777, they were consequential months. He was there for the surrender of Fort Ticonderoga to the British in July of that year, and for the strategic victory of the Continental Army in Saratoga, NY that followed a few months later. He served again in the militia later in his life (1794-1800), and rose to the rank of Colonel.

Moses and his friend Aaron Kimball homesteaded for a time on this property in Reading before he brought his wife to live with him there. Maybe Aaron helped hew those beams and fell those hemlock joists? Moses must have shared stories with his son about how hard they worked “back in the old days”. Isn’t that how it always goes? George recounts a few stories of how far his father and Aaron traveled for supplies, and tells of “one time after having hoed corn all day for General Chase at Cornish, each took a bundle of young apple trees and bore them home by moonlight twelve miles upon their backs.”

Old apple trees still dot the land. I have wondered about their provenance. Now I wonder whether they are descendants of the ones perched on Moses’ back all those years ago. And yes, I have arranged to have a few apple trees genotyped to see if they might be an interesting heirloom variety. Once a geneticist, always a geneticist.

One last note on Moses’s time–one that binds us specifically to this house and its history.

In the notes we received from the prior owners, there was mention of a certain Hosea Ballou having spent time at the house, noting he was a “prominent Universalist minister”. We are practicing Unitarian Universalists (UUs), a liberal religion that is characterized as a “free and responsible search for truth and meaning”. Unitarian Universalism was created by a merger of the Unitarians and the Universalists (didn’t see that coming, right?) in 1961. I am not a religious scholar, not even of my chosen faith, and so I asked my minister if she’d ever heard of Hosea Ballou. She looked slightly disappointed to realize I had no idea who he was, but assured me he was required reading for UU ministers in divinity school.

I have now come to know that Hosea Ballou was one of the most prominent theological writers and clergy of the American Universalists. He preached throughout the Upper Valley in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s before leaving to be minister of Second Church of Boston in 1817.

Still, I wondered at the veracity of the handwritten page that suggested he’d been to the house. And then I found George W. Chaplin’s telling, in which he recounts that his father’s “religious convictions were of the liberal Faith, and he was a great admirer of the Elder Hosea Ballou who during his residence in Barnard, on several occasions held meetings at his house, in Reading.”

It is fun to imagine Hosea Ballou passing through the same doorway I did this morning, and engaging people in the ideas of a budding liberal faith.

George closes his account of his father this way: “He was a man of generous impulses and labored assiduously for the promotion of peace and good order in society. To the poor and destitute he was liberal to a fault, often dispensing to others beyond his ability to bestow, in view of a safe and necessary economy. To his children he was a wise and faithful parent and counsellor…” and then some more.

He has decidedly less to say about his mother–mostly chronological facts. Gilbert Asa Davis’s account is full of this sort of male oriented history. Sign of the times, to be sure. Ah, patriarchy.

Still, concerning Moses….even if he earned a little grade inflation from an adoring son, he certainly sounds like a heck of a guy. The kind you might like to have a beer with. Or maybe a switchel.

I will eventually return to the story of people who lived in the house after Moses and Mary and their children.

But for now, let me just say this: There were people who suggested early in our journey that we might be better off just tearing down the house and starting over. They got to us too late. We’d already fallen in love with the house and its history.

So, the number 1782 will stay, and invite curiosity.

The house will stay.

And we will invest time and treasure to prepare it to shepherd new stories, and more history, for what we hope is at least another 240 years.

The task won’t be simple. The house needs a lot of work to get to where we want it to be in terms of energy efficient operations, and health and comfort, as a sustainable, durable building.

And that is for another post.

I grew up with Melinda Ballou in Lexington. It wasn’t until many years later that I learned her family dated back to revolutionary times. I’m guessing she’s a descendant of your Hosea Ballou. I will find out because I’m a great fan of small-worldisms.

Great stories! Do you know about the antique apple collection at the Tower Hill botanical garden near Worcester? Could be worth a visit.